What About Unsigned Wills?

What makes a will valid in British Columbia? What makes an amendment to a will valid?

These deceptively simple questions can require surprisingly tricky answers. A complete answer is beyond the scope of a brief article like this, but in this post, we will look at some recent cases that involve the Supreme Court of British Columbia (the “Court”) tackling the question of whether a document that does not meet the usual requirements for validity should be recognized as a valid will or amendment to a will.

There are a number of formalities usually required to have a document recognized as a valid will in British Columbia. The Wills, Estates and Succession Act (“WESA”) appears to set them out relatively clearly in section 37, titled “How to make a valid will,” which states:

(1) To be valid, a will must be

(a) in writing,

(b) signed at its end by the will-maker, or the signature at the end must be acknowledged by the will-maker as his or hers, in the presence of 2 or more witnesses present at the same time, and

(c) signed by 2 or more of the witnesses in the presence of the will-maker.

Section 54 (1) states that to make a valid alteration to a will the alteration must be made in the same way that a valid will is made under section 37.

Seems simple enough. That is not the end of the story though. There are many pitfalls for the unwary, such as restrictions on who may be witnesses. For example, beneficiaries and executors should not witness a will or amendment to a will. Those types of considerations are, however, not the focus of this post. Instead, we will be looking at the implications of section 37(2)(a) and section 54(3).

Section 37(2)(a) and section 54(3) provide that a will or alteration to a will may be valid, despite not meeting the usual requirements, if the court orders it to be effective under section 58.

Section 58(3) states:

even though the making, revocation, alteration or revival of a will does not comply with this Act, the court may, as the circumstances require, order that a record or document or writing or marking on a will or document be fully effective as though it had been made

(a) as the will or part of the will of the deceased person,

(b) as a revocation, alteration or revival of a will of the deceased person, or

(c) as the testamentary intention of the deceased person.

The cases we will be discussing in this post involved the application of section 58 and presented the Court with the following two questions:

- Should an unsigned will draft be recognized as a valid will?

- Should an unsigned note be recognized as a valid amendment to a will?

The first of these cases, Bishop Estate v Sheardown[1], (“Bishop Estate”) did not seem to attract much comment in the media, but certainly did amongst lawyers working with wills and estates. The deceased, a Ms. Marilyn Bishop, put a will in place in 2013. Ms. Bishop later worked with a lawyer in 2020 to draft a new will. Unfortunately, in large part due to restrictions resulting from the pandemic, Ms. Bishop cancelled the appointment she had scheduled to sign the draft will. Sadly, she passed a few months later having never signed it.

In her 2013 will, Ms. Bishop left the bulk of her estate to Kelowna General Hospital Foundation. The 2020 draft, prepared by her lawyer based on her instructions, made no provision for Kelowna General Hospital Foundation and instead directed the bulk of her estate to her nephew and niece-in-law.

In Bishop Estate, the Court was ultimately satisfied that the unexecuted 2020 will represented “Ms. Bishop’s fixed and final intentions for the disposal of her assets.” The Court, therefore, upheld the unsigned 2020 will draft as fully effective as though it had been Ms. Bishop’s validly executed will.

This result hinged on the very particular circumstances of the case. The effect of pandemic-related restrictions on Ms. Bishop’s ability to meet with her lawyer to sign the draft will played a central role in the Court’s decision. Nevertheless, the ruling is an excellent illustration of the kinds of considerations the Court may weigh when deciding whether to exercise the power to uphold a document that fails to satisfy the formalities generally required.

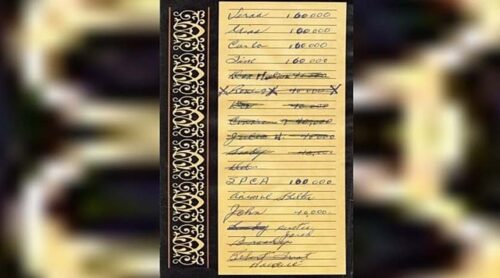

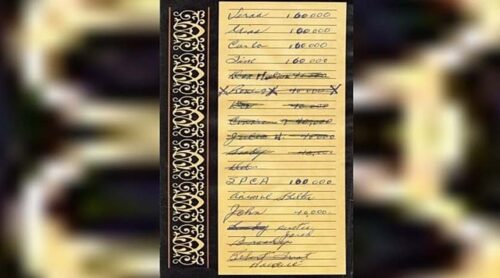

The second of these cases you may have seen in the news media. Henderson v Myler[2] involved consideration of whether an unsigned handwritten note should be upheld as a valid alteration of a will. In this case, a Ms. Eleena Murray put a will in place in 2013. In that will, she gifted nearly $1.4 million, the bulk of her nearly $2 million estate, to the BC SPCA.

After her passing, several of Ms. Murray’s relatives asked the Court to uphold a handwritten note that they asserted represented her intention to amend her 2013 will. These changes would significantly reduce the gift to the BC SPCA to $100,000 and make several other adjustments to which of her relatives would benefit from her estate and how much they would receive. In particular, the note appears to direct the bulk of her estate to three of her nephews who were not provided for in her 2013 will.

This is a copy of the note:

(photo credit: BC Supreme Court / CBC)

Ultimately, the Court concluded that the evidence did not support a finding that the note represented the fixed and final intention of Ms. Murray to change or alter her 2013 will. It, therefore, held that the note was not effective as a valid codicil or alteration to the will. In reaching that conclusion, the Honourable Madam Justice MacNaughton, at paragraphs 280 – 299, provided a detailed analysis of the factors weighing for and against recognizing the note as valid under section 58 of WESA. Similarly, in Bishop Estate, The Honourable Madam Justice Matthews provided a detailed explanation of the circumstances supporting upholding the unsigned draft as a valid will.

Taken together, these two judgments help to give some sense of when the Court may and may not be willing to recognize a document that does not meet the usual formality requirements. We will be closely following how section 58, and these two cases, are used in the future and will post updates as the law in this area evolves. In the meantime, these two cases also serve as great examples of why it is always better to do what one can to leave a clear, up-to-date, and valid will. As we have said in previous posts, leaving it to the court to guess what one’s testamentary intentions were after the fact can be quite costly and unpredictable.

[1] 2021 BCSC 1571 (CanLII), <https://www.canlii.org/en/bc/bcsc/doc/2021/2021bcsc1571/2021bcsc1571.html>

[2] 2021 BCSC 1649 (CanLII), <https://www.canlii.org/en/bc/bcsc/doc/2021/2021bcsc1649/2021bcsc1649.html>